Faculty of Bioscience Engineering – Earth and Life Institute

Challenges

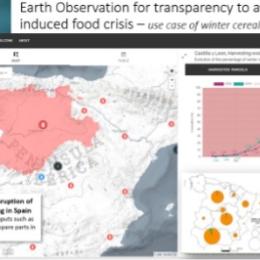

Following the lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a fear that wheat crops (cereals) would not be harvested on time, severely disrupting the availability of foodstuffs. Would combine-harvesters be able to harvest all the crops before the wheat started to rot? Would repairs of these agricultural machines, which operate day and night, still be possible given that the supply chains for spare parts were in complete lockdown? Would the farmers who drive these magnificent machines survive COVID in large numbers?

UCLouvain’s contribution

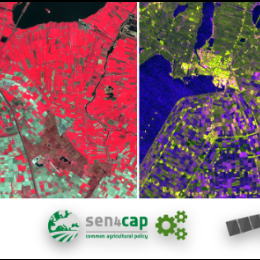

At the request of the European Commission, the Geomatics Laboratory of the Earth and Life Institute led by Professor Pierre Defourny has developed methods for the real-time monitoring of agricultural parcels using the newest European satellites. Its open source system, called Sen4CAP and which is financed by the European Space Agency (ESA), automatically processes optical satellite imagery (capturing light from the sun that is reflected from the surface of earth) and radar satellite imagery (with radar satellites emitting their own energy and measuring the reflected signals).

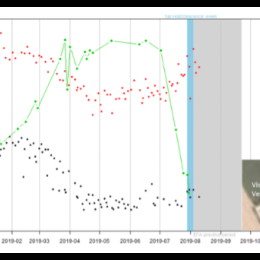

At the start of the lockdown, NASA and ESA feared that a food crisis might only compound the health crisis. They decided to monitor the progress of the wheat harvest in real time, starting in Spain, the first country to harvest this cereal which is of seminal importance to the world. They chose Sen4CAP, which is operated by UCLouvain, to process huge amounts of satellite imagery using cloud servers. A race against time began to identify all the wheat fields and monitor the harvest. To check whether the harvests were progressing normally, they had to study the progress of the 2019 harvest season in the same way. Every week, researchers updated the number of fields that had been harvested on the NASA-ESA Rapid Action Dashboard. This was the first time that a crop harvest had been tracked parcel by parcel in real time for an entire country. Moreover, this had to be done for two years in one go, in record time, and remotely at that!

Week after week, month after month, the statistics for each Spanish region were collated. Ultimately, 100% of wheat fields were harvested on time. The pandemic thus posed no threat to our pasta and bread supplies for the coming years as the granaries are more than full !